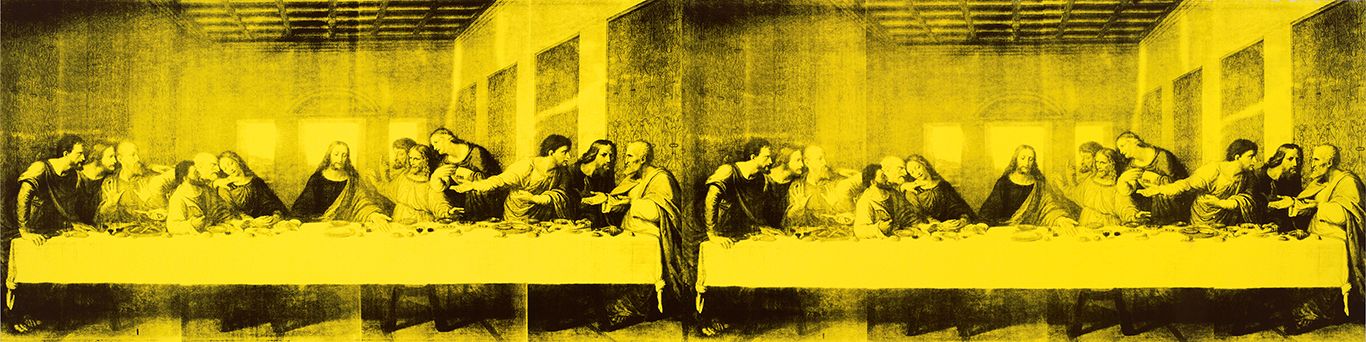

The art trade on both sides of the Atlantic has been abuzz with sales from permanent collections at public institutions, otherwise known as deaccessioning. Most prominent in the recent debate about associated ethics is the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). The institution offered major works – by Brice Marden (3, 1987 – 88), Clyfford Still (1957-G, 1957) and Andy Warhol (The Last Supper, 1986) – for sale at Sotheby’s in October 2020 with a combined estimate of 65 million USD. Just hours before the Marden and Still paintings were due to hit the block (the Warhol was to be offered privately), the museum withdrew both from the auction in response to a growing maelstrom of negative criticism, internal and external.

The BMA was technically operating within the bounds of newly loosened regulation from the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) in America: a targeted, finite response to the ongoing pandemic which has, to all extents and purposes, obliterated gate receipts from museum balance sheets. Funds from the sale would be directed towards ongoing running costs (even though the museum was not in financial distress), ‘care of the collection’ and, crucially, new acquisitions to diversify the collection of a major museum rooted in a city with a 65% black population. The museum director had even secured public consensus from the executive director of the AAMD before proceeding with the proposed deaccessions.

Operating within the rules, with admirable objectives, the plan was still deemed controversial enough to attract bitter criticism from all sectors of the art world and, further, controversial enough to spook the institution into withdrawing the works from public sale. Why?

Long seen as one of the unassailable taboos in the UK museum sector, and generally handled with judicious caution in America, two key factors have contributed to a temporary loosening of the strict ethical codes surrounding the practice. The first is the decimation of visitor numbers to museums due to the global pandemic. The second is a growing sense of urgency, especially in American cities with black majority populations, to develop public collections which reflect the diversity of society at large.

Permanent collections housed by museums, often accumulated over decades or even centuries through a patchwork of philanthropic gifts, bequests or acquisitions, are generally intended to be just that. Caroline Douglas, Director of the Contemporary Art Society (CAS), an organisation that acquires work on behalf of their partner museums in the UK, explains: ‘Museums are the forever proposition – that’s why artists want to be in them.’ Gifts to museums, whether from an individual or an organisation such as the CAS, are usually given with the explicit proviso that such works must remain part of the collection in perpetuity.

In both America and the UK, professional membership organisations publish guidelines of best practice for their member institutions. While rules vary, there are a few broad points of consensus. Until the global pandemic, one of the most common restrictions was that works could not be sold to keep the lights on. Deaccessions – sales from the permanent collections – might be allowed where works fell outside an institution’s ‘core collection’ and with the rigorously enforced purpose of funding new acquisitions. In other words, funds raised must be reinvested back into the collection.

There is subsequently a dual aspect to the question of deaccessions: why is the work being sold? And what will the funds be spent on? Having a defensible answer for one part of this equation isn’t enough. Institutions must make a clear case for the acceptability of a sale, and there are subsequent restrictions – both written and unwritten – pertaining to the use of sale proceeds.

The risk of eroding donor confidence in the entire museum sector underpins much of the regulation at play. Not only are museums usually charities or non-profits with beneficial tax codes, they are also typically built on the generosity of private citizens and the state. Selling works from the collection – given on the explicit or implied understanding that they would remain the collection forever – is therefore seen as a grave betrayal of the trust placed in them by donors. It subsequently threatens to dismantle faith in the very mechanisms and structures which maintain museums as viable economic entities in the first place.

There is another great risk with museum deaccessions. Tastes change, fashions come and go. The world evolves. While some artists may appear utterly irrelevant to the present moment, they may come to be seen as pivotal by later generations. And what might appear frivolous and inconsequential in one historical era might be understood as prescient and vital by museum audiences of the next. There also remains – most pertinently in the case of the BMA, but generally for museums in Western Europe and America – the question of representation and the art historical canon.

It’s clear to today’s audiences that the ‘approved’ art historical account of the post-colonial age needs expansion, revision and rewriting. But it’s also impossible for anyone to know what the cultural consciousness of the future might deem important. The mission of the museum is, therefore, inherently conservative: to hold, intact, collections intended for the public good. The prevailing taste which forms a public collection is likewise, in and of itself, a historical artefact.

Similarly, selling the work of living artists can have a profoundly negative impact on their market and career trajectory. While museum acquisitions are the gold standard of validation for an artist, sale of their work from a museum, logically, can have the opposite effect. Essentially suggesting that an artist is, in the eyes of the museum (the custodians and narrators of art history) no longer of consequence. To make such a dramatic, public and negative statement about an artist’s work goes entirely contrary to what is widely understood as the Hippocratic Oath of museums vis-à-vis the wellbeing of the artistic community it serves.

2020 has shown everyone – inside and outside the art world – that systems, structures and rules that previously seemed immutable are in fact entirely contingent. Many public institutions have survived this year with furlough schemes, goodwill and inventive short term strategies. But they can’t live on vapours alone. The Victoria & Albert Museum, for example, received 15% of its usual traffic in August. Such precipitous drops in visitor numbers are untenable. Museums need donations yes, but most importantly they need an audience, gate receipts, successful gift shops and humming cafes. Another long stretch into 2021 without this revenue will bring financial distress, just as public borrowing hits record highs in the UK and the glamourous social events which generously lubricate the cogs of private philanthropy remain strictly off limits. We can therefore only foresee more – not less – works coming to market from the museum sector next year. Outcry or no outcry, reality must bite sooner or later. The debate continues.

Image 1: Image credit Sotheby’s; Image 2: Image credit Baltimore Museum of Art; Image 3: Image credit Amir Hamja/Bloomberg via Getty Images; Image 4: Image credit Katherine Hardy/The Art Newspaper; Image 5: Image credit Baltimore Museum of Art