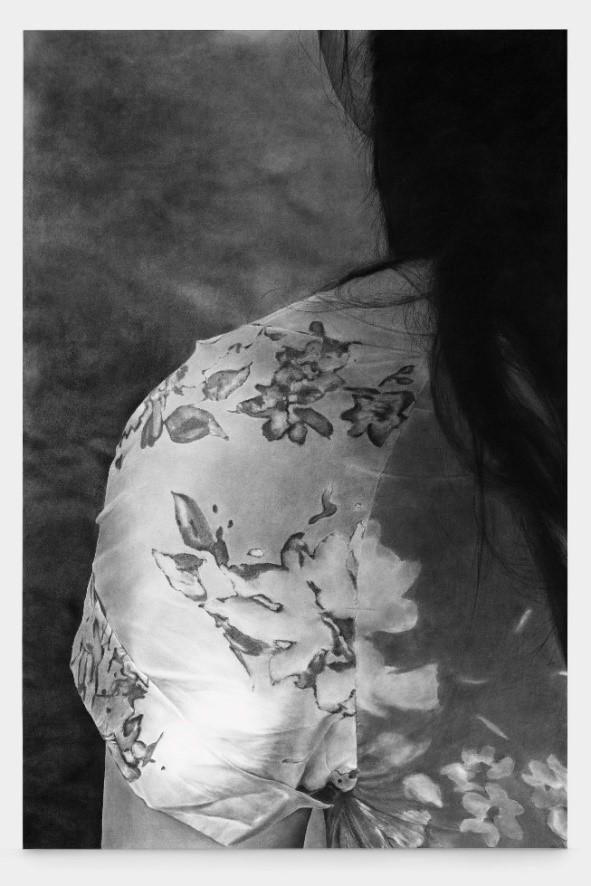

Paris-based Chinese artist Alexandre Zhu (b. 1993) creates strikingly hyper-realistic works using only charcoal, gesso and varnish. His large-scale compositions are imbued with depth and texture, achieving an almost sculptural presence despite their two-dimensional form. Recently, Zhu’s atmospheric seascapes and introspective portraits have garnered attention, with exhibitions at Paris Internationale, NADA Paris, Victoria Miro in Venice, and Art Basel Hong Kong—signalling his growing recognition and market potential.

One chilly February afternoon, Advisory Coordinator Margaret Rand had the pleasure of speaking with Zhu over Zoom to discuss his practice and upcoming exhibitions.

Spending his childhood between Shanghai and Paris, Zhu initially became drawn to charcoal during his first year of art school at École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs (ENSAD) in Paris. Drawn to its tactile nature, describing the charcoal as “simply dust,” Zhu developed his distinctive technique—sanding layers of handmade gesso to create the ideal ground before applying his charcoal and varnishing the surface for a velvety texture.

These monochrome compositions feature imagery from his personal memories or photos, cropped to emphasize the soft curvature of machinery, the glimmering crests of waves, or the delicate wrinkles in his loved ones’ clothing. These enlarged forms envelope the artist as he works, challenging his perception and understanding of form to such an extent he must “rest [his] eyes every fifteen to twenty minutes.” Employing unconventional materials such as makeup sponges and bubble wrap, Zhu shifts and moulds the “dust” to conjure his nostalgic, ashy memories that reveal few—if any—traces of hand or gesture.

Zhu’s early charcoal series started around a specific narrative, capturing Shanghai’s changing environment where he grew up. His first series Leviathan (2022) features close-up images of the machinery tied to construction sites. These works root themselves in Zhu’s personal history, traveling frequently between Paris and Shanghai, and witnessing the fast-paced urban transformation of China. In our interview, Zhu revealed how he “wouldn’t recognize the places [he] once knew,” infatuated by the rapid reinvention of his hometown. This investigation into China’s urbanisation is a prevalent theme throughout Chinese art over the past several years, similarly investigated by notable contemporaries like Liu Wei, Ding Yi and Zhang Ruyi. By enlarging and cropping this machinery, Zhu isolates the ambiguous fragments, often fleeting and overlooked, within the greater process of building. Stripped away from any recognizable function and detached from any specific context, this raw imagery of metal and steel relies on feeling, rather than clear representation, to invoke meaning.

The soft dust particles and subtle shifts in grey tones are accentuated by the artist’s intentional use of a limited black-and-white palette, intended to create distance between the artist and the work. To Zhu, “colour means choosing, sometimes emotions.” By deliberately limiting his palette, the artist leaves the power in the viewer’s unique experience of the work. This deliberate limitation in colour and form, along with his photorealistic style, reflect Zhu’s broader artistic approach, focusing on the raw impact of his composition.

While investigating Zhu’s work, I noticed that most of his series are named after mythological creatures or gods. His Leviathan series is named after the primordial sea serpent from ancient mythology, known to symbolize world destruction, alongside reconstruction and renewal. This duality mirrors the rapid transformation Zhu observes in his own city, a process of continuous upheaval and rebirth. It is this very duality that Zhu evokes in his fragmented images. By isolating and obscuring parts of machinery by focusing on extreme close-ups, he seeks to recapture their forms as if they were alive— “sometimes tender, sometimes aggressive”—evoking the shifting, dynamic essence of these objects in the context of change.

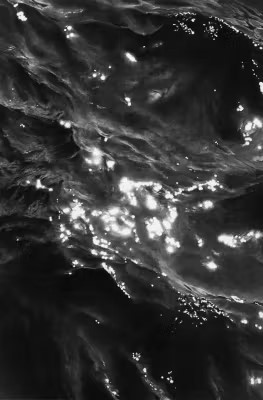

This dualism is further seen in Zhu’s later series of seascapes. The artist’s 2024 Hadal Series is named after the Greek god of the dead and king of the underworld Hades. Here, Zhu continues to capture the core sentiments of the changing world around him within these seemingly “neutral images.” These seascapes serve as a larger metaphor for the simultaneous beauty and ominous quality of the ocean. His velvet-like surfaces soak up the viewer into their lush, glistening waves, while the deep black charcoal overwhelms, perhaps akin to the overpowering radiance of Yves Klein’s Blue. According to Zhu, “the closed and tight cropping is meant to remove information and context, evoking [his] gaze of a fleeting moment and trying to leave the viewer in his own perception of a personal memory, through [his] own.” Similar to the machinery in Zhu’s Leviathan Series, these seascapes deliberately lack any time zones or specific contexts. Rather, they are driven by the all-encompassing textural elements of each body of water, captured in the large-scale composition.

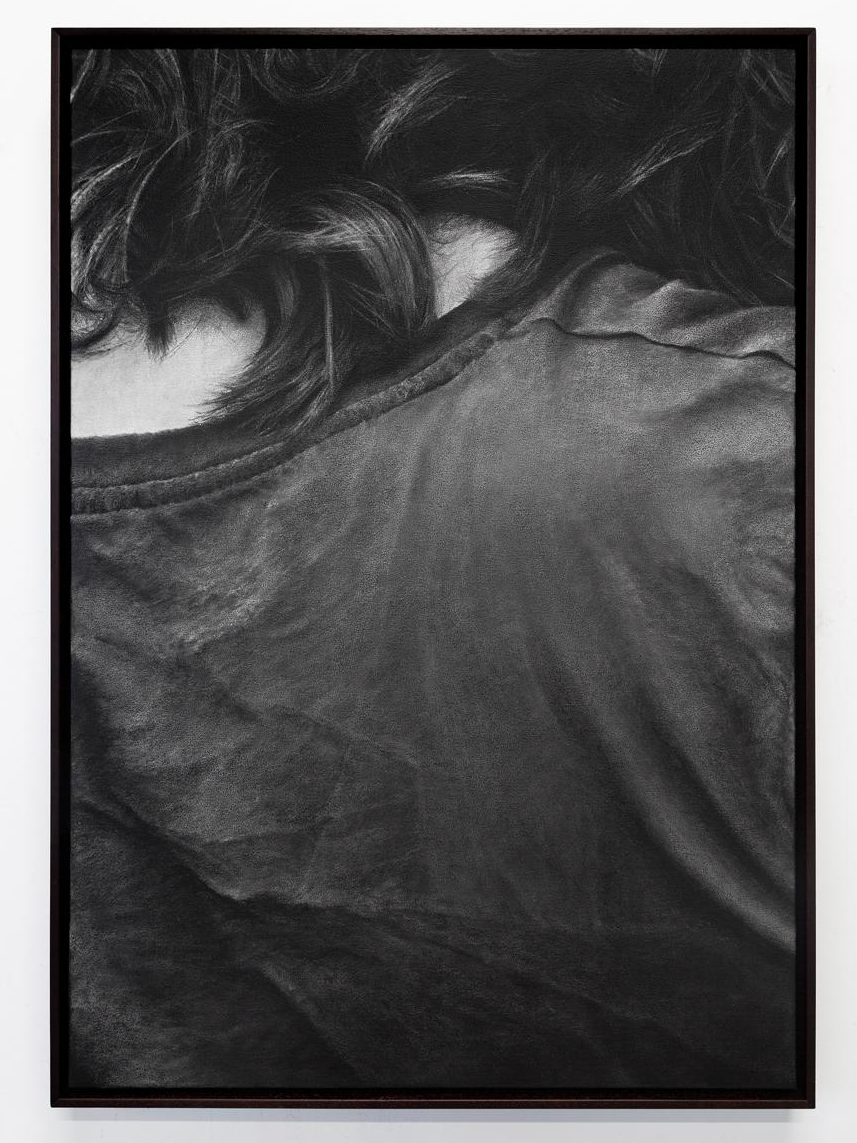

In his most recent works, Zhu has transitioned toward more personal subject matter, focusing on intimate portrayals of his loved ones from behind. This unique perspective builds on the artist’s Leviathan and Hadal series, honing into detailed fragments of his subjects. This new body of work was first exhibited at the Paris Internationale fair, concurrent with Art Basel Paris Plus, with Shanghai-based Gallery Vacancy. The titular work Ma (2024) is a close-up of the artist’s mother, featuring solely her left shoulder and part of her hair. Her blouse’s floral design folds in rhythm with the fabric’s wrinkles and bulges, while delicate strands of hair sweep down, framing the upper right section of the canvas. Zhu became tired of working in series and felt a strong need to tap into more personal subject matter as he began to work on multiple, different images at the same time, blending intimate portraits alongside his urban and natural landscapes. It is here that Zhu has begun to turn back to more narrative compositions, revisiting personal memories based on images of loved ones to accompany his charcoal environments. As such, simultaneously on display to his new series at Paris Internationale were Zhu’s seminal seascapes at NADA Paris with London-based Night Café Gallery.

Another piece from this new body of work, They’ll never know (2) (2025) is currently on view in Vacancy’s booth at Art Basel Hong Kong. Here, Zhu continues to play with the relationship between title and composition, capturing the balance between intimacy and anonymity. The title They’ll never know adds an emotional weight to the work, hinting at the unspoken moments and unshared connections that exist behind closed doors. The blurred details of the figure, combined with Zhu’s meticulous charcoal technique, evoke a sense of longing and memory, inviting viewers to project their own experiences onto the ambiguous scene. This exploration of private moments against the backdrop of Zhu’s signature charcoal landscapes marks a poignant evolution in his work, as he moves away from abstract forms and towards a more direct, emotional connection with his subjects.

Zhu’s transition away from rigid series and toward more varied compositions suggests a maturing artistic vision, one that is both timeless in his investigations and innovative in his unconventional materiality. With continued exposure at key fairs and galleries, we are eager to see how Zhu’s artistic practice will continue to develop.

Paris Internationale 2024

Art Basel Hong Kong 2025

In a recent ARTnews article, “It’s Too Early to Know if Fed’s Interest Rate Cut Will Revive a Flagging Art Market, Experts Say” Philip Hoffman, founder of The Fine Art Group, weighed in on the Federal Reserve’s half-point interest rate reduction. While Hoffman acknowledges the move as positive, he suggests that a further one to two percent drop is needed before significant corrections in the art market occur. He describes the upcoming auction season as a “chicken and egg” situation, with cautious buyers and sellers waiting for better economic conditions and clarity on future tax policies.

Read the full article on ARTnews here.

Written by Henry Little, Director, Art Advisory; Charlie Wood, Associate Director, Art Advisory; Grace England, Researcher

INTRODUCTION

The Asking Price #1 – November 3rd, 2022

The Fine Art Group is pleased to present The Asking Price, a new monthly newsletter focused on the global art market.

Drawing upon world leading expertise, The Asking Price offers regular insight into the complex world of art dealers, art fairs and auction houses.

For our inaugural edition:

- Henry Little interviews Matthew Travers, Director of Piano Nobile in London, discussing the gallery’s comprehensive survey of Frank Auerbach portraits (7 minute read)

- Grace England covers British painter Glenn Brown’s new private museum, The Brown Collection, exploring the wider trend of self-funded artist museums (6 minute read)

- Charlie Wood provides incisive analysis of the Frieze week auction sales, highlighting some of the most important sales and developments (5 minute read)

INTERVIEW WITH MATTHEW TRAVERS

BY HENRY LITTLE (7 MINUTE READ)

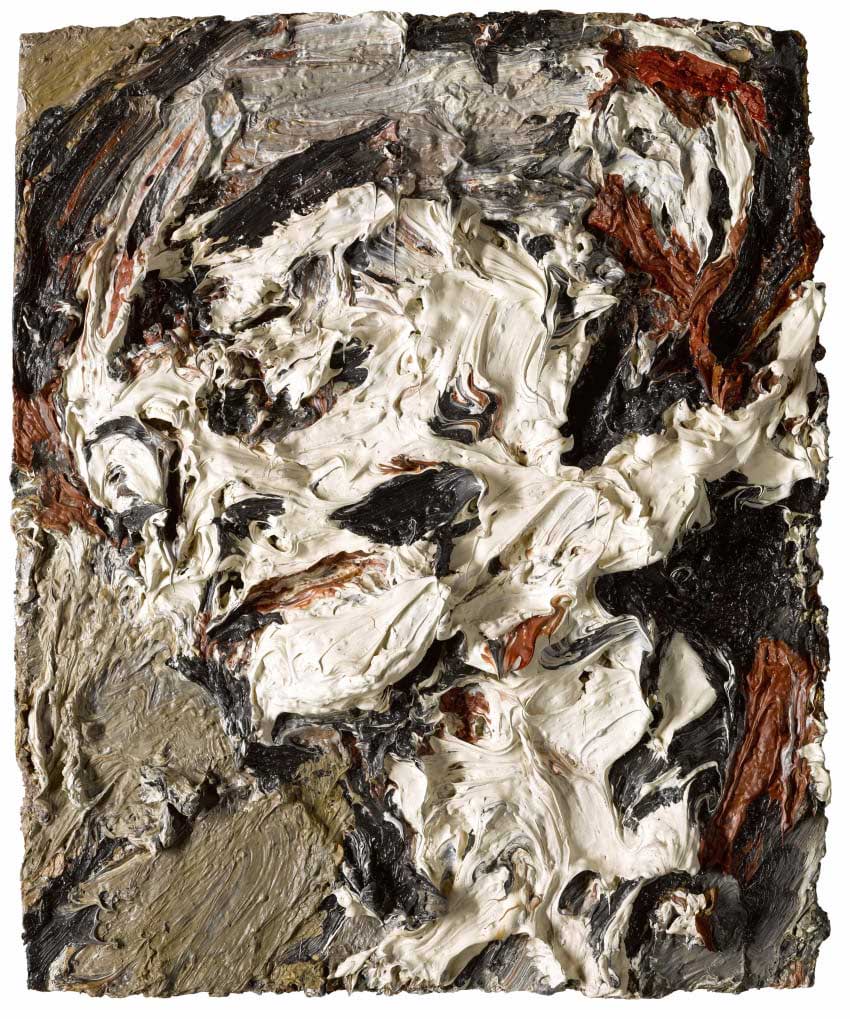

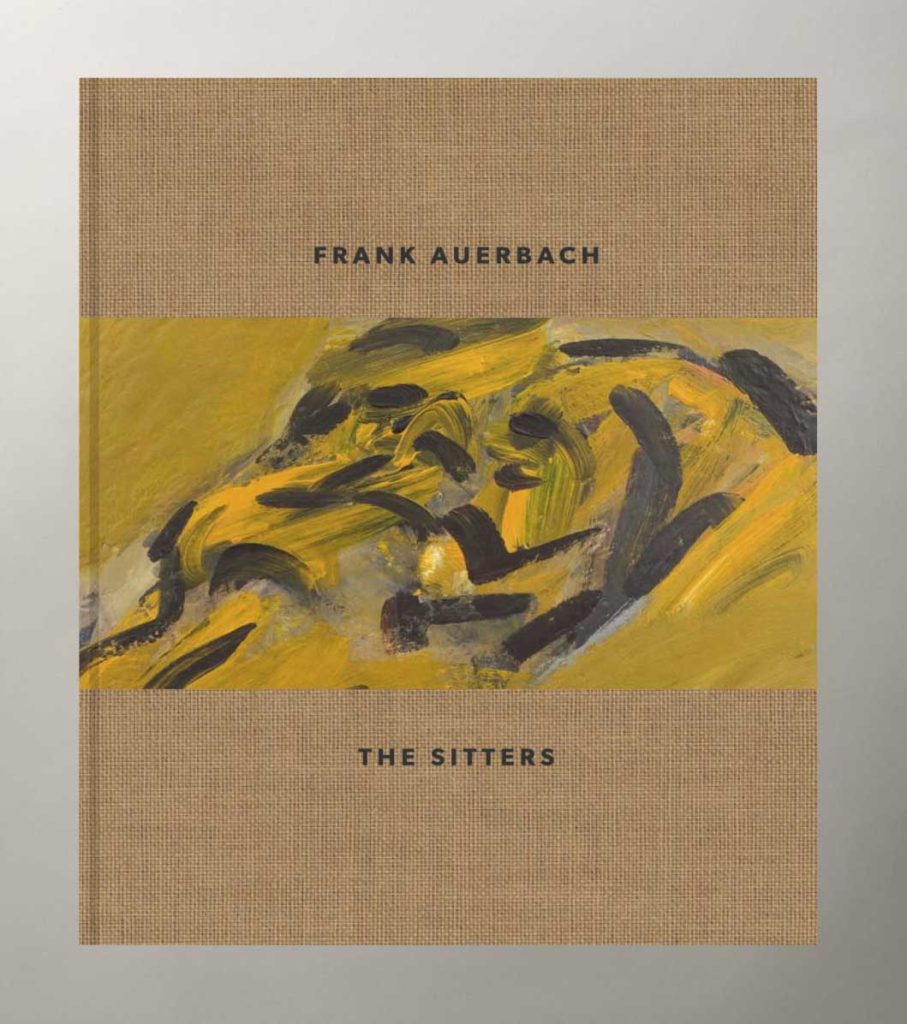

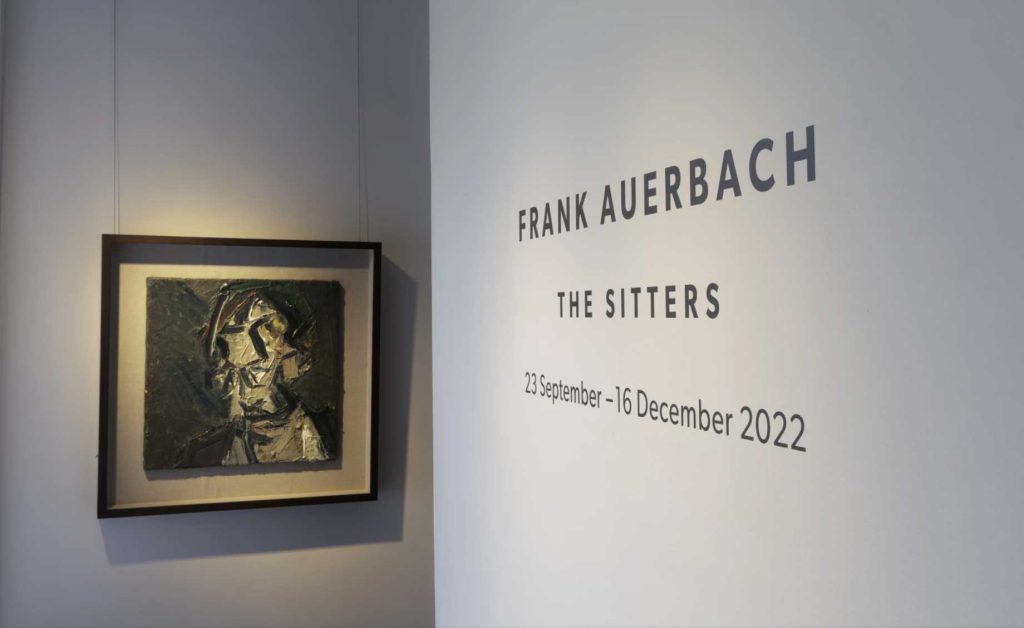

Known for their distinguished taste, Piano Nobile specializes in 20th Century British art. Until Dec. 16, the gallery hosts Frank Auerbach: The Sitters, a wide-ranging survey of the celebrated nonagenarian painter’s portrait heads from 1956 to 2020.

We spoke to Matthew Travers, Director at Piano Nobile, about the process of preparing such an important exhibition, writing catalogues and the nuances of the artist’s market.

Henry Little: You’re currently hosting a major survey of Frank Auerbach’s portrait heads, offering a survey of the artist’s work from 1956 to 2020. Could you describe the process of developing and mounting an exhibition like this? With so many important works there must be a long lead time for such a considered presentation.

Matthew Travers: We love presenting this type of exhibition, particularly for artists whose work we handle regularly. It’s important to find a moment to celebrate the artist because that has two purposes. One, to be able to enjoy them and see them together, and the other, to allow our audience, if they know the work very well, to understand it better. For an audience that doesn’t know it so well, we can introduce them to the work in a deeper way.

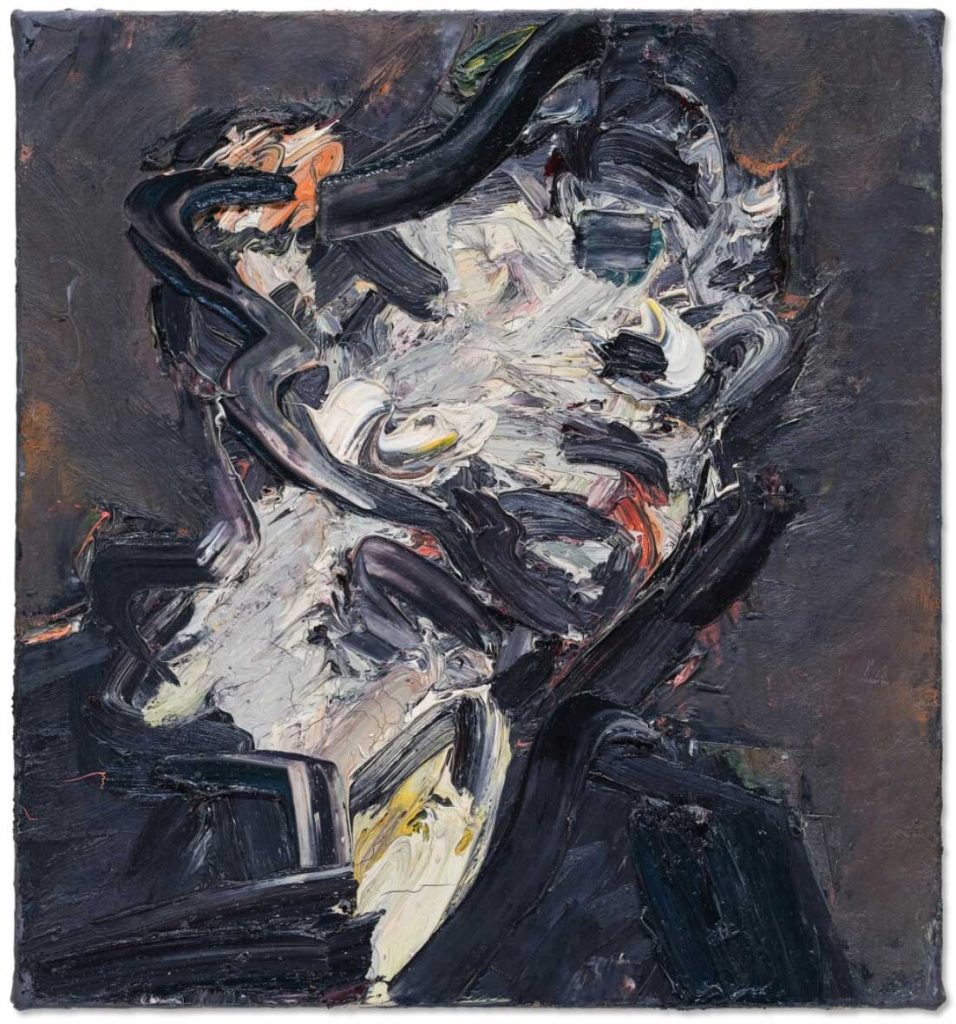

Even for someone like Frank Auerbach, to see a concise, consecutive body of work is not necessarily that easy unless there’s a major museum retrospective, so that was the thinking behind it. We’ve been thinking about shows like this for a long time, and we isolated the idea that we wanted to present a show of the portrait heads. For me, they’re some of his greatest works. They’ve got an amazing intensity and power. Of course, the landscapes are incredible, large and beautiful things, and that could be another exhibition entirely. But it was really the heads that we wanted to start with. It’s always about a 12-month lead time from fixing a date to gathering the works and getting the catalogue together. From a press point of view, timing is very important.

Then it’s a case of acquiring works for gallery stock, which we do all the time, and building up a base of works we know we can structure the show around, but then also leaning on the generosity of lenders, and being able to pull a major group of works together. It would be impossible to go into the market and pull together 40 major Frank Auerbachs from across his career that tell a story and are tightly curated. So, it’s very much down to the generosity of owners, whether it be existing clients we sold to or talking to people who have works.

It’s amazing how generous people are prepared to be, and the understanding is that a show like this is only a good thing for everybody. It adds great provenance to a work, it’s wonderful to see it published in a new publication, and it celebrates a painter and develops the world’s understanding of him. These things make people very happy to loan. Often people hear we’re doing a show and voluntarily offer things to us; some great works came to us that way for this exhibition. We often borrow from museums as well; that’s sometimes a longer process. You need a good lead time to achieve that, at least 12 or sometimes 24 months.

One of the great USPs of this show is that all the works come from private collections so they’re works you wouldn’t generally see. I think that’s a wonderful thing to do: to bring a body of work together that not only speaks of the artist and his development throughout his career, but also brings fresh work into the public eye that hasn’t been seen for decades publicly. Visitors can look at them in a relaxed, quiet environment, where they can get up close to works, study them and not be distracted by the larger spaces of a public museum or large gallery space. Smaller works, domestic-size works, life-size works, as in Frank Auerbach heads, can always feel very powerful, but are made to feel rather small in huge spaces.

Showing them in smaller rooms speaks very much to the way they were painted, whether it’s particularly for London school, whether it’s Kossoff or Bacon. Bacon’s studio was tiny. Freud worked in domestic spaces. These works were made in London rooms, in London spaces, in the proportions of London houses; therefore, to show them in that type of space only enhances them and the viewing experience.

HL: What purpose do such exhibitions fulfill for the gallery? How do they help build your reputation for specialist expertise?

MT: We have a clear focus on London School painting. Many works come in and out behind the scenes that the world never sees, so to take a moment to celebrate this painter is exciting. From our point of view, it helps a wider public see the breadth and body of work that we’ve handled over the last few years and, of course, works are for sale. It helps a wider public understand what the gallery is up to. Roughly a third of the show is for sale. For an artist such as Auerbach, works appear sporadically in isolation, in the auction sales, at an art fair or in a gallery. But coming to an exhibition with works available from the early 1960s, all the way through to a recent work by Frank from 2020 is special.

To have that choice gives collectors an amazing opportunity to think about buying Auerbach, to compare a body of available work. It’s important to isolate what makes collectors tick and understand which area of the artist’s work appeals to them.

The early work has a hugely important presence within his career, people love it, and traditionally the values have been highest there. But he’s an amazingly consistent painter. I would argue his entire oeuvre is exceptional and within that, it’s natural to have preferences. Some collectors prefer the 1980s, 1990s or the 2000s over the darker, heavier, more angst ridden 1950s and 1960s paintings. That’s personal preference and there’s no right or wrong. To look at all aspects of that and have works within that, that are available, is a big part of the exhibition for us and offering that service to clients and collectors.

HL: Why did you think now was the right time to stage such a meticulously curated show?

MT: When presenting a tightly curated show such as this, timing is important. There have been many shows of Frank’s work in the past, whether large or small, which are more general retrospectives. But he comes out of the wider London School and ultimately the post-war period is about the depiction of the human form, finding new ways of depicting the human form in a post-war world. Surprising as it may sound, we believe this is the first-ever show dedicated to Auerbach’s portrait heads.

That’s why we settled on it and were intent on keeping the curation tight, with a concise body of work from the 1950s through 2020. We have presented paintings and drawings from every decade of the artist’s career that chart changes in sitters from the early works. E.O.W., Gerda Boehm, to Catherine Lampert, the most recent sitter being William Feaver, who has been sitting for over 30 years. Julia Auerbach has been the longest standing sitter, with works from 1960, and his most prominent muse in recent years.

We have, therefore, been quite selective and have not just shown a group of works we can easily secure. Producing something that makes sense, that is not overly weighted in one place and not others, is key to it, and also stands the test of time.

HL: Can you explain how you piece together your exhibition catalogues, the role they play and what you think about when writing texts for such publications?

MT: The catalogues play a huge role in the exhibition. The exhibition is transitory and is here for a couple of months. But then it is gone, and the works go back out into the world. Publishing is a very important aspect of what the gallery does. Every time we produce a catalogue, it is more than just a record of the exhibition. It becomes a reference point for us and collectors.

We wish to produce something that is a meaningful addition to the artist’s literature and ultimately which supports, enriches and promotes the artists in which we’re interested. This catalogue has a previously unpublished interview with the artist and Martin Gayford. We republished an important text by Michael Podro, a great friend of Auerbach. Michael was a wonderful art historian and writer on Auerbach’s work. So many important writings on artists in their lifetime were published in obscure places. Our catalogue is now the most accessible place to find this essay and it still rings true today, even though he wrote it 50 years ago.

Another aspect of the catalogue is to provide a comprehensive record of Frank’s sitters, as this is the focus of the show. We thought it constructive to compile a full list with information on each of them, roughly 40 in total. It also builds a timeline. The earliest sitters were Leon Kossoff and Stella West. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were several short-term sitters. But then, as with the early works, the later works are refined back down to half a dozen regular sitters, who have been sitting for 30 or 40 years.

The sitters would have regular appointments in the studio once a week, often for two-hour sessions, where Frank would paint them. The work would then be pulled out a week later, scraped down and repainted. Sometimes 20 or 30 sittings, which could mean 20 or 30 weeks of sittings, if not longer, for a work to be produced. This is an incredible regimen, enforced by the artist, which is a true partnership with the sitter.

HL: How does Frank’s exhibition fit within the gallery’s wider program?

MT: We specialize in 20th century British art, positioned in the wider context of American and European artists. Britain certainly wasn’t working in isolation. The gallery mounted a show in 2020 titled Drawn to Paper: Degas to Rego, looking at Parisian School painters. We often handle the work of Giacometti or Degas, occasionally Picasso or Léger, because these artists did have an important effect on British painting, like Dalí and British Surrealism. Another aspect of this specialism is British figurative painting from Sickert until today. An important part of that history, that lineage, is post-war London painting, the School of London as Kitaj dubbed it.

It felt like the right moment to mount this exhibition. It could have been something we did in a few years’ time, but it was wonderful to have Frank’s involvement. So it’s part of our wider positioning of celebrating London School painting.

HL: What are the greatest pleasures of bringing together such a historic group of works?

MT: To live with them and study them only adds to one’s expertise on the artist, and one’s assurance when advising and buying in the future. Especially understanding why works are great, what aspects one is looking for in different periods, and what one might look for from a condition point of view. This is incredibly informative and enjoyable, bringing a deep satisfaction in realizing a compelling group of paintings.

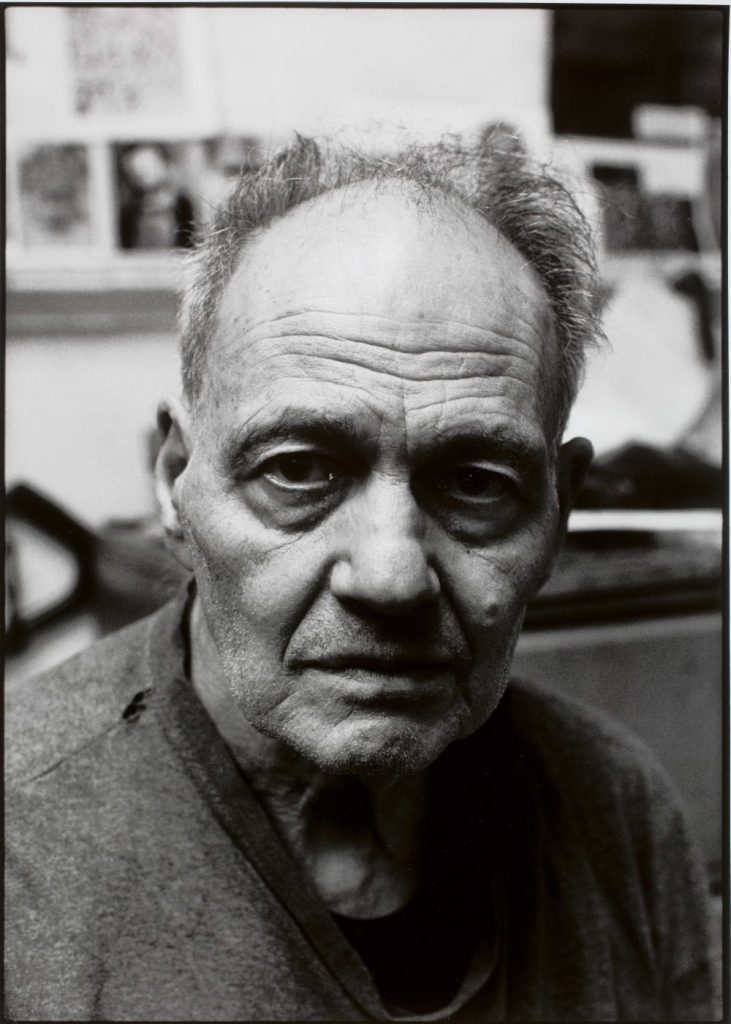

HL: Can you elaborate on the concurrent presentation of Nicola Bensley’s photographs, Frank Auerbach: A Morning in the Studio, and how they complement the wider exhibition?

MT: For any exhibition, it’s always a dream to find unpublished photographs of the artist that have never been seen. In this case, we spoke to Nicola, a great photographer. She went to visit Auerbach in 2015 for a morning, making works in natural daylight from black and white 35-mm film. She took several iconic images of Auerbach at the age of 87, looking like he could be a man in his fifties.

This is testament to the power and strength of the man. Not just of the mind, but physically. Oil paint is heavy and hard to manipulate, particularly when scraping it off.

HL: Can you provide indicative price ranges for available works in the exhibition?

MT: Auerbach’s works are highly sought after. The show ranges from £250,000 for a 1980s or 1990s charcoal, to multiple millions for earlier heads. Recently, the artist’s Head of JYM (1984-85) sold at Sotheby’s for a record public price of £5.65 million (including premium). His market has grown organically and is therefore incredibly robust. The new catalogue raisonné now runs to 2022, providing greater clarity on extant work. These are beautiful, rare things and they will only become more sought after with time.

We find our clients for Auerbach are totally global, whether it’s from the US, East Asia, Europe, Middle East and Africa, South Africa, or South America. They are all over the world and he touches on something very broad, very human, which has a totally international appeal and will continue to do so.

Two works, which sum up the exhibition for me, are from totally different periods. Sixty years apart, they are both for sale: the early charcoal from 1960 of Julia, Auerbach’s wife, and the last work we are showing, Reclining Head of Julia, from 2020. To see his longest standing sitter, Julia, 60 years apart, has a powerful resonance. Together, they demonstrate a trajectory which is ultimately redemptive of a young man dealing with the horrors inflicted by the Second World War, losing his parents and being uprooted from his place of birth, Berlin, and moving to England. In this beautiful late work of his wife Julia, she is afflicted with all the pains of old age but there is a kind of peace to it.

THE RISE OF THE ARTIST MUSEUM

BY GRACE ENGLAND (6 MINUTE READ)

THE GLENN BROWN COLLECTION

Among the hundreds of events, private views and shows which launched during Frieze Week (as well as the fair itself), British artist Glenn Brown opened his own self-funded museum, The Brown Collection. Tucked away in a mews off Marylebone High Street, Brown says he hopes the collection will introduce his work to a larger audience and provide visitors with a haven to sit, read and relax. Announced a month ago, The Brown Collection will initially exhibit the artist’s own work, with plans over time to bring in pieces from other artists in Brown’s personal collection.

A mix of sculptures, paintings and drawings from Brown’s oeuvre, the collection is housed in Bentwick Mews, a property the artist purchased six years ago. Having originally planned to use the house for a studio office, Brown instead made the decision to restore and convert the building into an archive and exhibition space frustrated, he said, by the fact that “people couldn’t see my work in London.” Indeed, while Brown is widely collected and included in major public collections throughout the UK, including the Tate, British Museum and Arts Council, he has not had a major institutional show in Britain for some years, his last large-scale retrospective taking place at Tate Liverpool in 2009 (later touring to museums in Turin and Budapest).

Bemoaning the rotation of commercial shows as too slow (especially given the transnational nature of Brown’s market), Brown has opened this new venture close to The Wallace Collection, a museum housing many masterpieces which have inspired his own practice (a must-see is his version of Fragonard’s Blue Boy). While Brown’s work is sought after on both the public and private market, the Brown Collection’s impressive capacity is largely due to a tendency by the artist to retain as much of his own work as possible. The artist is also known to buy back some of his earlier, more historic pieces.

Glenn Brown is the latest example of a growing number of artists who have founded and self-funded museums of their own work. While many single-artist foundations have been established posthumously (with examples including The Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City, Musée Picasso in Málaga and Paris, and Musée Courbet in Ornans) a select few have been founded by the artists themselves in their lifetimes.

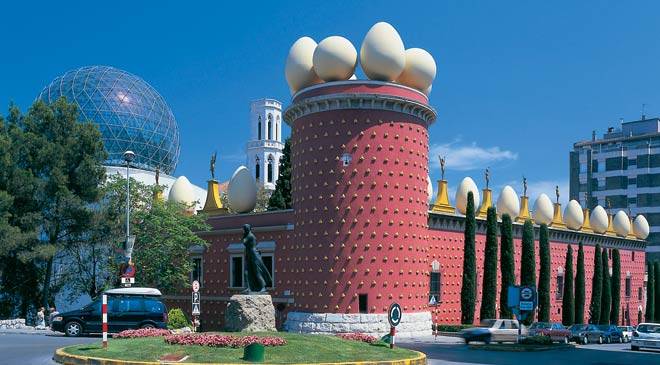

One of the most impressive (and bizarre) “artist-museums” is the Dali Theatre and Museum in Dali’s hometown of Figueres, Spain. Conceived in the 1960s by Dali and the Mayor of Figueres, Dali took over the ruins of the town’s municipal theatre in the 1970s, a building of sentimental value where Dali had held the first ever exhibition of his work. The Dali Theatre-Museum officially opened in 1974 and, as well as housing over 1,000 works by Dali, is considered a Surrealist masterpiece, with every aspect of the architecture and interior designed by Dali himself. These include some suitably wacky features, including the Mae West Room, an installation when viewed from a certain angle forms the ‘face’ of the famous actress. The artist’s burial crypt sits at the center of the museum.

Establishing a legacy, and having control over that legacy, seems to be the crux of the artist-museum. Yayoi Kusama, currently the world’s most expensive living female artist, opened her own museum in her home city of Tokyo in 2017. Operated as the principal project of her foundation, its aim (according to the museum director) is to offer “visitors a chance to learn about the courageous battles that Kusama has fought as an avant-garde artist, allowing them to experience and feel the sincerity of her ideas.” As an artist who faced a great deal of sexism and xenophobia early in her career, and who has battled mental health problems for most of her adult life, establishing her own controlled and curated space seems to have been the paramount motivation.

A fear of mortality is also a key factor when artists decide to transition from creative to curator. British artist Tracey Emin recently underwent an intense battle with bladder cancer and the disease came close to claiming her life. In September 2021, after undergoing extensive surgery, Emin announced that she would turn her Margate studio into a museum after her death. Partly inspired by a visit to Marfa, Texas, where she saw the Donald Judd Foundation building, Emin decided she wanted a place to house her extensive archive of works, photographs and essays, as well as her own collection of “other people’s art.”

In January 2022, Emin announced the establishment of a museum and art school. Launched in October 2022, TKE Studios provides 30 affordable artist studios, as well as an 18-month artist residency funded by the Tracey Emin Foundation. A former mortuary, which sits near the 30,000-square-foot converted bathhouse, the property will also serve as a small museum for Emin’s enormous archive of 30,000 photographs and some 2,500 works on paper.

The growing popularity of the artist-museum is perhaps the latest step for contemporary artists choosing to exercise greater autonomy over their image. At a time when the artist’s public persona is increasingly scrutinized, with cancel culture, social media and gallery hierarchies having the power to make or break an artist, the artist-museum allows artists to regain some control over how they might be perceived.

Indeed, foundations which have chosen to establish single-artist museums posthumously have often been met by the dilemmas of inheritance struggles, legal disputes and family conflict. The most prominent example is the Picasso Family which has endured numerous disputes for decades. Most recently, plans for a new Picasso Museum in Aix-en-Provenance were abandoned in September 2020 after three-year negotiations between the town council and Picasso’s stepdaughter Catherine Hutin-Blay collapsed.

By choosing to establish open collections in their lifetimes, prominent public-facing artists like Brown, Emin and Kusama can avoid some of the misrepresentations of legacy and the dispersal of personal collections which can often follow death. Reflecting on the creation of her new artist studios, residency and museum, Emin remarked: “When I was ill, I thought I was going to die. A part of me asked, what’s it all about? What am I here for? What am I doing? I knew I could do so much more, but I wasn’t sure what it was. And then the whole thing made perfect sense. If we can get one person here that becomes a really good, amazing artist, I’ve done my job.”

From the sentimental to the truly fantastical, no matter what form it takes, the artist-museum has emerged as a powerful phenomenon.

FRIEZE WEEK 2022 ROUND UP

BY CHARLIE WOOD (5 MINUTE READ)

AUCTIONS ANALYSIS

The Frieze Week London auctions opened to a backdrop of jitters surrounding uncertainty around UK government policy and the falling pound. Overall, however, the sales were a success for all the major houses, selling squarely within or above their presale estimates. Sotheby’s lead the total at £96 million ($107 million), the highest result for its October sales in seven years. Christie’s followed with £72.5 million ($82.2 million), which beat its 2021 Frieze total, and Phillips was at £18.7 million ($20.9 million).

All of them achieved strong sell-through rates ranging from 94-100%, but the sales were tightly managed with several withdrawals from each house ahead of time, helping to ensure strong final statistics.

There was much speculation regarding a potential increase of international buyers piling in due to the falling pound, and while there was significant international bidding, data released by the houses reflected broadly similar levels to last year. American and Asian bidding continues to be hugely important to the results of these sales and they remain firmly scheduled to conveniently capture both time zones, despite disrupting schedules for those also at Frieze.

Christie’s evening sale demonstrated significant Asian bidding: one paddle bid on over 10 lots and was a huge support to the sale. Likewise, Sotheby’s had strong levels of American bidding which drove the prices for several top lots, notably Gerhard Richter’s “first abstract painting” 192 Farben (1966) which sold for £18.3 million premium ($20.5 million) against an estimate of £13 – 18 million.

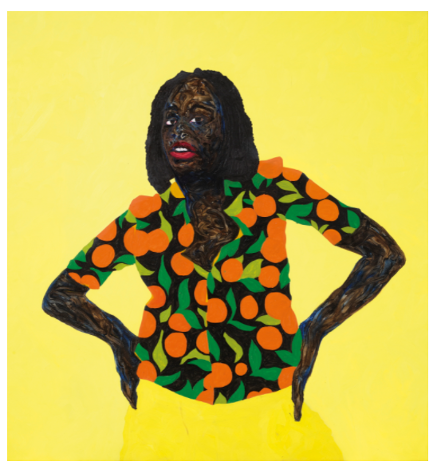

Young contemporary artists continue to show market strength. Phillips, always strongest in this area, ensured its sale was much more focussed towards this category with fewer Impressionist & Modern lots offered this season despite previously venturing into these collecting categories. Several artists making their auction debut, including Julian Pace and Rebecca Ness, significantly outperformed their estimates.

High prices were also achieved for Flora Yukhnovich and Caroline Walker, but there was notably calmer bidding for other artists in this category, including Jadé Fadojutimi, Christina Quarles and Shara Hughes. Not necessarily reflective of waning demand, estimates for many of these artists have now significantly increased, therefore, hammer prices are falling closer to their pre-sale expectations rather than vastly outreaching them as per previous sale cycles.

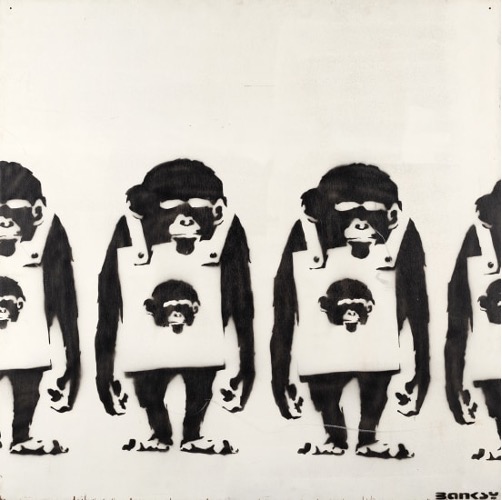

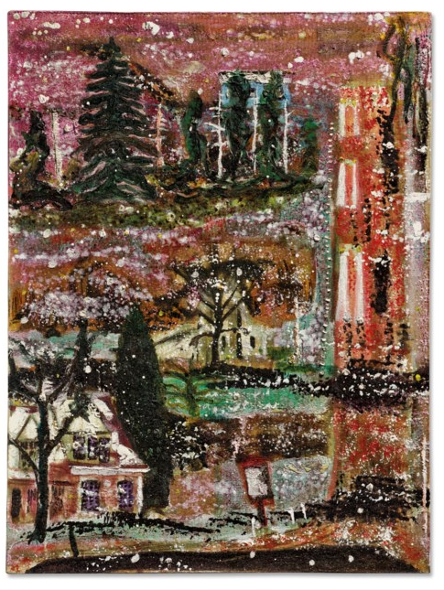

There were strong results for several blue-chip paintings throughout the week. David Hockney’s unusual landscape Early Morning Saint-Maxime (1968 – 69) vastly exceeded expectations at Christie’s, selling for £20.8 million premium ($23.7 million), double its high estimate. Richter’s cloud painting, Study for Clouds (Green-blue) (1971), also performed well at Christie’s with a result of £11.17 million premium ($12.7 million). Bidding was notably thinner, often with just two buyers battling it out, suggesting that demand at the very top level could be tightening. Two top-priced Banksy works fell significantly below expectations as price levels have, perhaps, reached an unsustainable level.

Top-priced works sold nonetheless; several key trade buyers made opportunistic purchases. The Nahmads acquired Christie’s Francis Bacon Painting 1990 (1990) below estimate; it hammered at £5,950,000 ($6.6 million) below a £7 million low estimate. At such a sensible price the piece was undeniably an attractive option for inventory.

Notable auction records for the week include a new record for a Tracey Emin painting set at Christie’s: Like a Cloud of Blood (2022) sold for £2.3 million premium ($2.6 million) against a £700,000 high estimate. New records were set at Phillips for Michaela Yearwood-Dan and Robert Nava. Sotheby’s set artist records for Louise Giovanelli, Charlene von Heyl, Kiki Kogelnik, Julien Nguyen, Caroline Walker and, most significantly, Frank Auerbach for his 1984 – 1985 Head of J.Y.M, achieving a new record of £5.6 million premium ($6.3 million).

5 EXHIBITIONS NOT TO MISS IN LONDON

Maximillian William – Somaya Critchlow, Afternoon’s Darkness

47 Mortimer Street, London, W1W 8HJ

Until 19th November 2022

Thomas Dane – Cecily Brown, Studio Pictures

3 Duke Street, London SW1Y 6BN

Until 17th December 2022

The Approach – Caitlin Keogh, Running Doggerel

1st Floor, 47 Approach Road, London, E2 9LY

Until 17th December 2022

Hayward Gallery – Strange Clay: Ceramics in Contemporary Art

Belvedere Road, London, SE1 8XX

Until 8th January 2023

Tate Modern – Cezanne

Bankside, London, SE1 9TG

Until 12th March 2023

TOP ART MARKET STORIES THIS MONTH

- Artists take to Instagram to criticize Gilbert & George’s claims that museums are now ‘woke’ and only focus on Black and women artists

- Frieze Opens to a Flood of Hungry Collectors, Calming Fears That Competition From Art Basel’s New Paris Fair Would Tank Attendance

- Paris+ par Art Basel’s VIP opening: galleries report good sales, the right people and a clear step up from Fiac

- Damien Hirst – The Currency: Is setting fire to millions of pounds worth of art a good idea?

- Opening Paul Allen’s Treasure Chest

LOOKING AHEAD

The highest value single owner sale to come to auction, the sale includes notable works by Botticelli, Canaletto, Cezanne, Lucian Freud, David Hockney, Gustav Klimt and Georges Seurat, spanning 500 years of art history.

All proceeds from the sale will be donated to charity.

FURTHER READING

- The Asking Price: Understanding Value 2

- Market Update: How the Art Market Joined the Digital Age

- Jan Prasens on Talking Galleries Panel Focus: Art Finance Debunked

OUR SERVICES

Offering expert Advisory across sectors, our dedicated Advisory and Sales Agency teams combine strategic insight with transparent advice to guide our clients seamlessly through the market. We always welcome the opportunity to discuss our strategies and services in depth.

The first round of 2022’s marquee evening sales took place in London last week with significant results. Sales totals from all three houses reached just over £400 million ($525 million), above 2019 pre-pandemic levels for the same period.

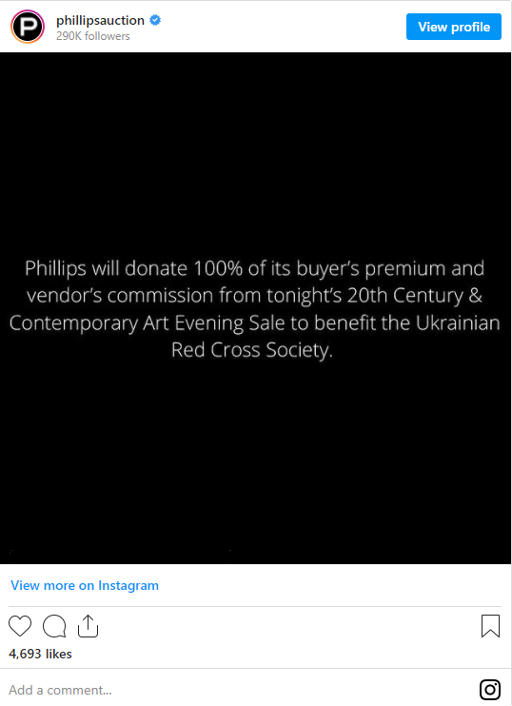

The ongoing crisis in Ukraine created an understandably strained atmosphere for all houses but the auctions continued with consummate professionalism. Phillips, owned by the Russian company The Mercury Group, especially came under fire, despite having no financial links to any of the sanctions imposed on Russian businesses. In response, Phillips donated all vendor’s commissions and buyer’s premium from their evening sale, totalling £5.8 million ($7.7 million), to the Ukrainian Red Cross Society. Christie’s made an announcement later in the week that they too would make a significant donation to the Red Cross efforts in Ukraine.

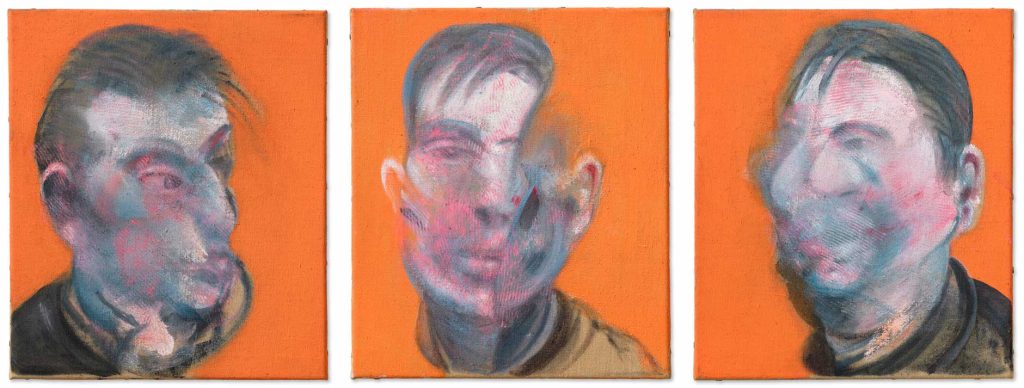

The top prices of the week were for Franz Marc’s recently restituted painting The Foxes (Die Füchse) (1913) which sold for a record £42.6 million ($56.8 million) premium. There was also a new record for René Magritte at Sotheby’s; L’empire des lumières (1961) sold for £59.4 million ($79.4 million) premium, almost tripling the artist’s previous record. Both works carried a guarantee, as did most top priced lots in the sales, including Francis Bacon’s Triptych (1986-87), which sold at Christie’s to the guarantor for £38.5 million ($51.2 million) premium. Guarantees accounted for about 64% of the overall sales total across the houses, with the total low estimates of guaranteed lots around £257 million ($337 million). This resulted in £249 million ($327 million) in guaranteed actual sales, signalling how crucial guarantees are in the current business, in terms of winning consignments as well as ensuring a high sell through rates for the overall sales figures.

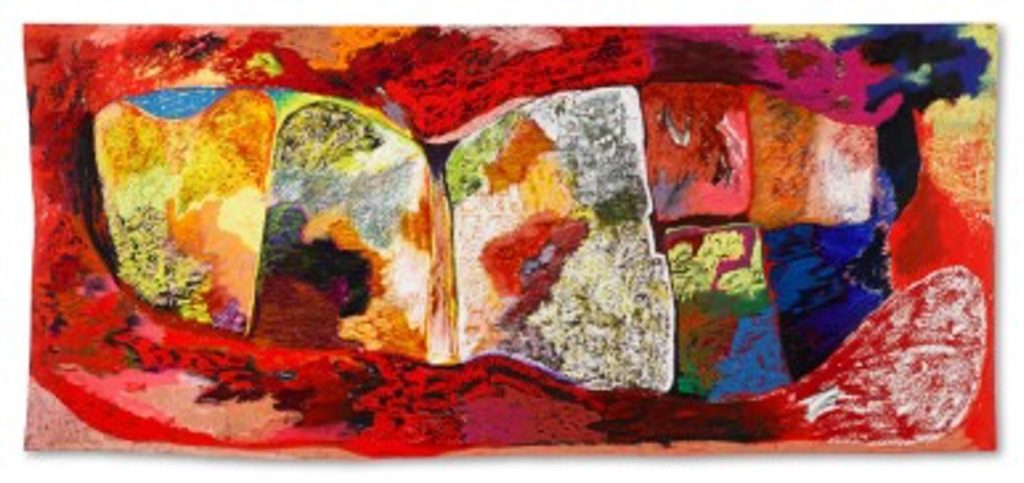

A slew of auction records were achieved for works from the newly coined ‘ultra-contemporary’ category, with new record prices set for Issy Wood, Shara Hughes, Flora Yukhnovich and Hilary Pecis, among others. This became the fastest growing auction category of 2021 and looks set to continue a strong trajectory for 2022. Two sales predominantly offered works from this category: Christie’s Shanghai Evening sale and Sotheby’s New Now Evening sale. 70% and 55% of their lots respectively sold above estimate, compared to around 25-30% in the Modern and Contemporary sales. The result for Rachel Jones who had her debut at Sotheby’s, selling for £617,400 ($828,600) premium against an estimate of just £50,000 – 70,000, felt particularly illustrative of the momentum in this area of the market.

Despite some very strong performances, a few disappointing results indicated that with secondary market supply increasing for some of these ‘hot’ artists, buyers are becoming somewhat selective about the lots they chase, as well as perhaps a waning appetite for the new price levels of these popular names. Amoako Boafo had four works at auction during the week, two of which sold on or below their low estimate. A work by one of the breakout stars of 2021, Salman Toor, was withdrawn from the Christie’s day sale, another in the Phillips day sale sold for one bid above the low estimate. While in no way does this indicate a slowing down of these artist’s markets (the works by Boafo that did sell well are now the second and third highest prices at auction) it suggests increasing selectivity as well as a possible plateau in terms of price points for these names that have on many occasions in the past twelve months far exceeded their estimates.

Another noticeable shift was a softening in demand for works by Banksy. With a total of ten works on offer across Phillips, Sotheby’s and Christie’s, at various price points, buyers could be discerning with the works they bid on. Together the works had a presale estimate of £14 – 21 million ($18 – 26 million) and the hammer total was just £7.5 million ($9.8 million). Four top priced pieces either went unsold or were withdrawn, significantly affecting the artist’s sales total for the week.

Despite the noticeable contrast in bidding between the ultra-contemporary and post-war and modern categories, this is not reflective of the latter’s slowing market. Their estimates represent very different price points, and, in some instances, several the highly priced lots were accompanied by estimates at the mid to top end of the artist’s market, which accordingly limits the amount of action and live bidding in the room. A number of these lots sold on one or two bids. Works that the market felt were under-priced, for example Peter Doig’s Some Houses on Iron Hill (1992), estimated at £600,000 – 800,000, were chased by buyers, with the work selling for £2.4 million ($3.3 million) premium.

Ultimately, despite the various categories performing at different levels, major auction records were achieved in both the modern and next generation contemporary segments. The exceptional sell through rates of all the auctions, ranging from 88% to 95%, is further testament to the overall strength of the market which proved resilient during a difficult week.